Understanding Barycentric Coordinates

Introduction

A nondegenerate triangle is a triangle where:

- All vertices are distinct

- The vertices do not all lie on a single line (Non-collinear vertices)

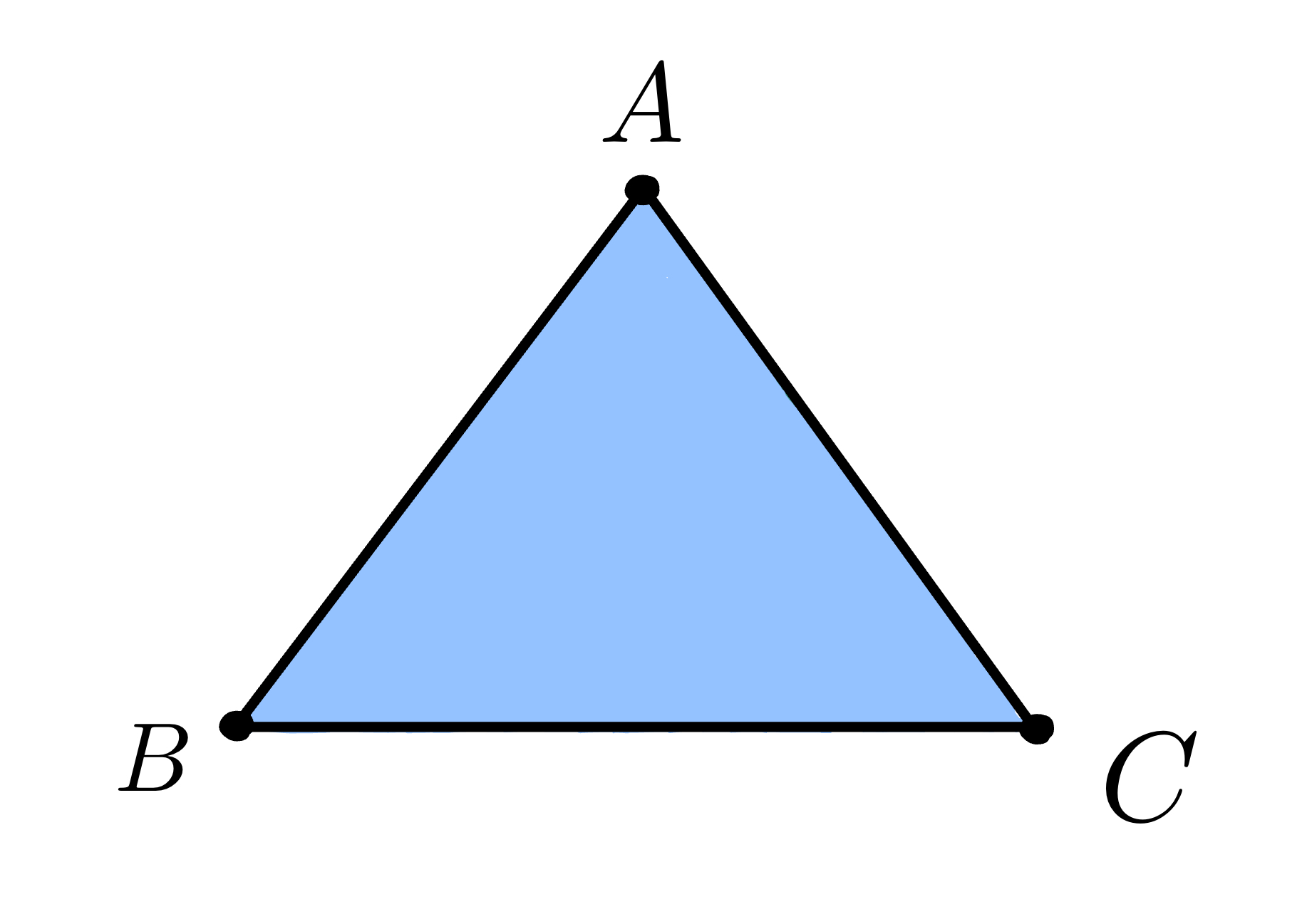

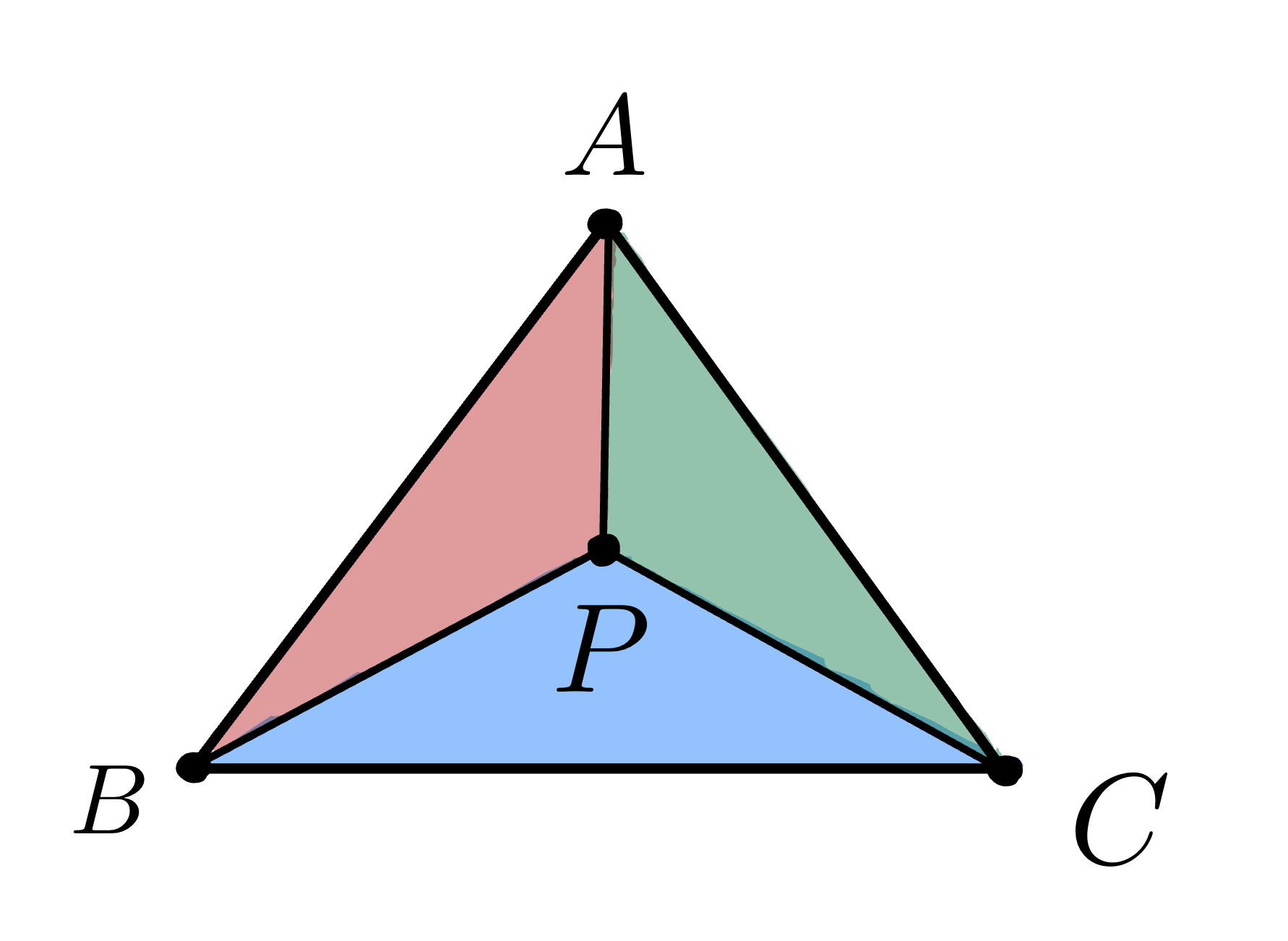

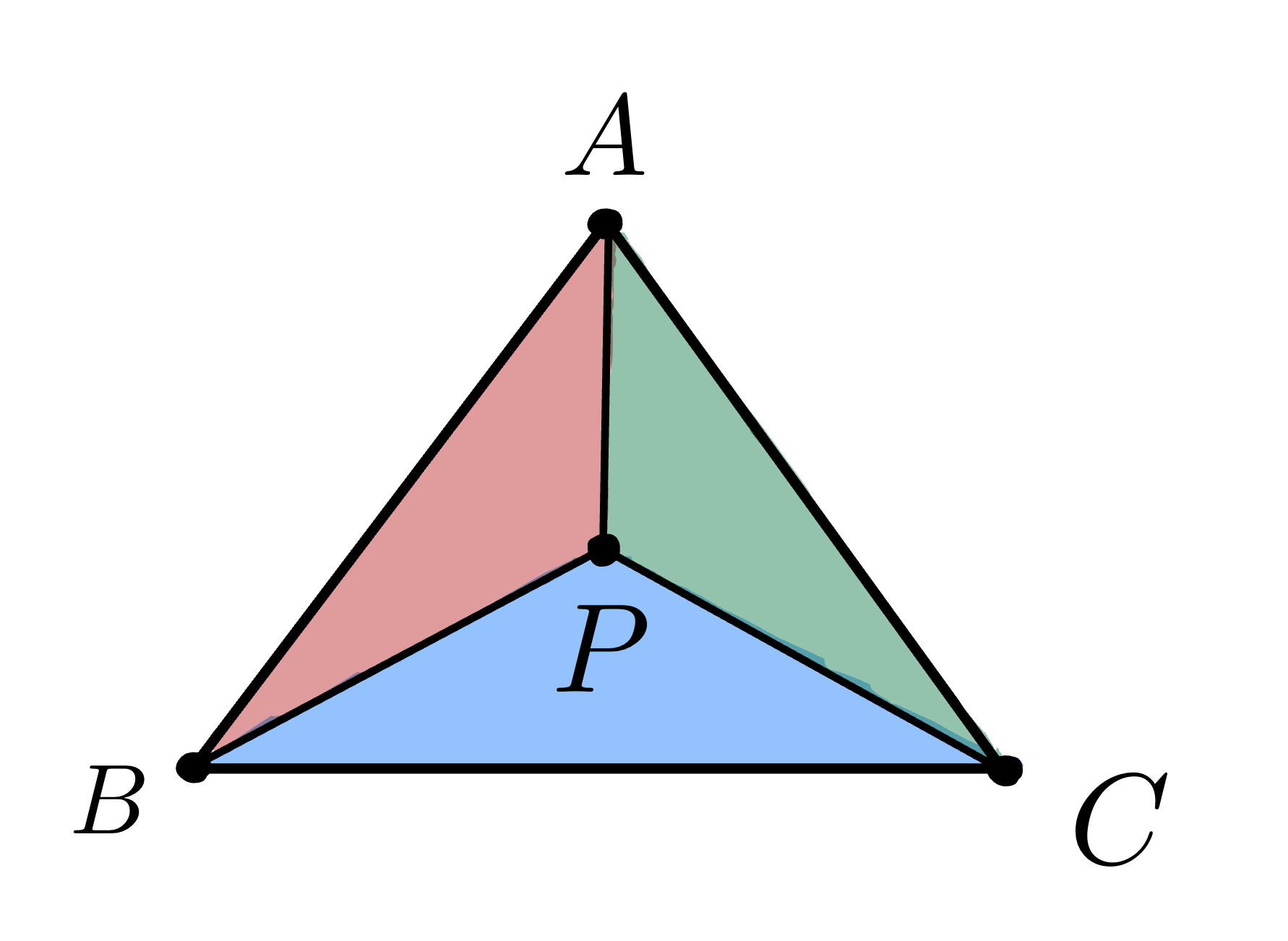

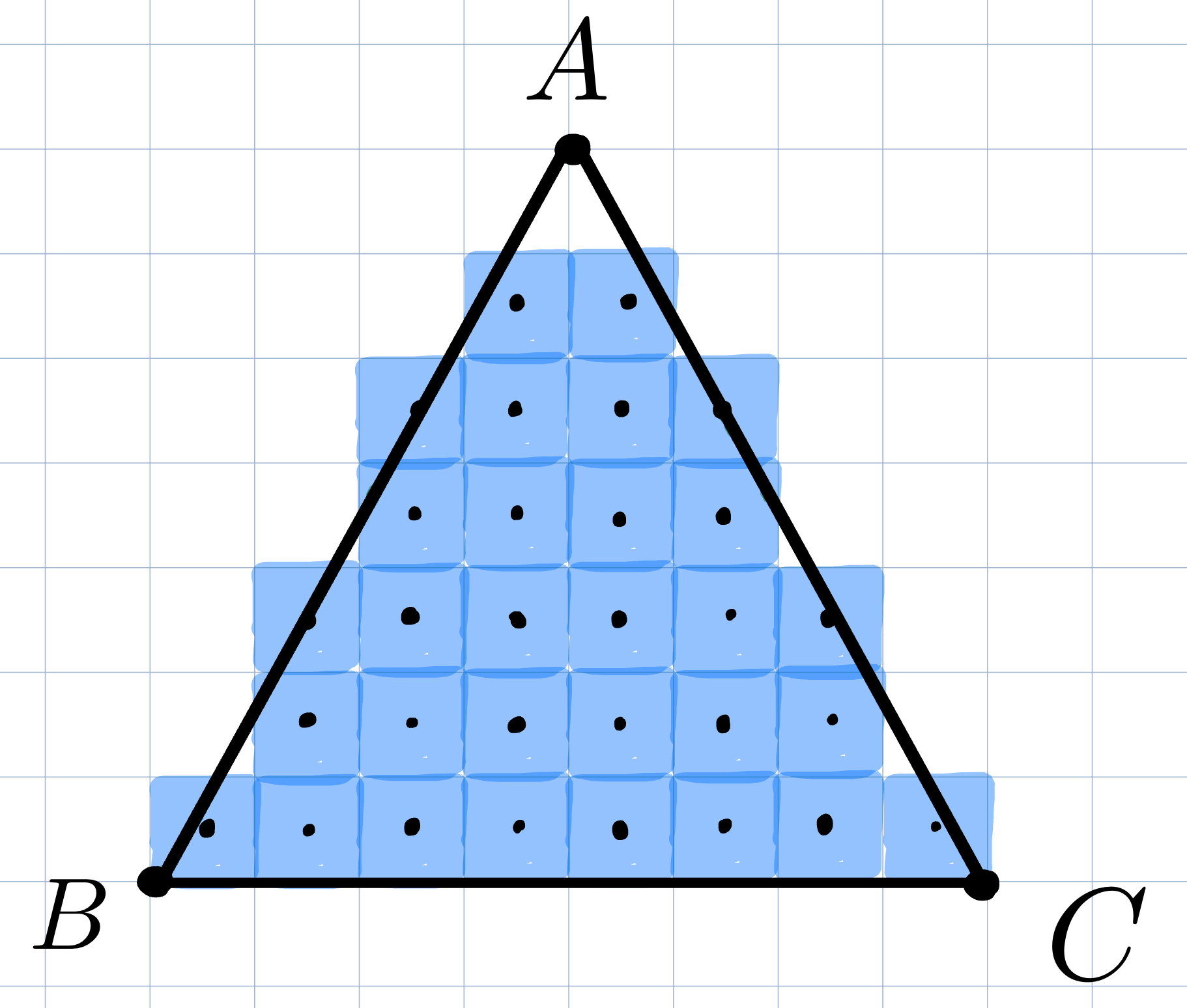

Consider the following nondegenerate triangle with vertices \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\).

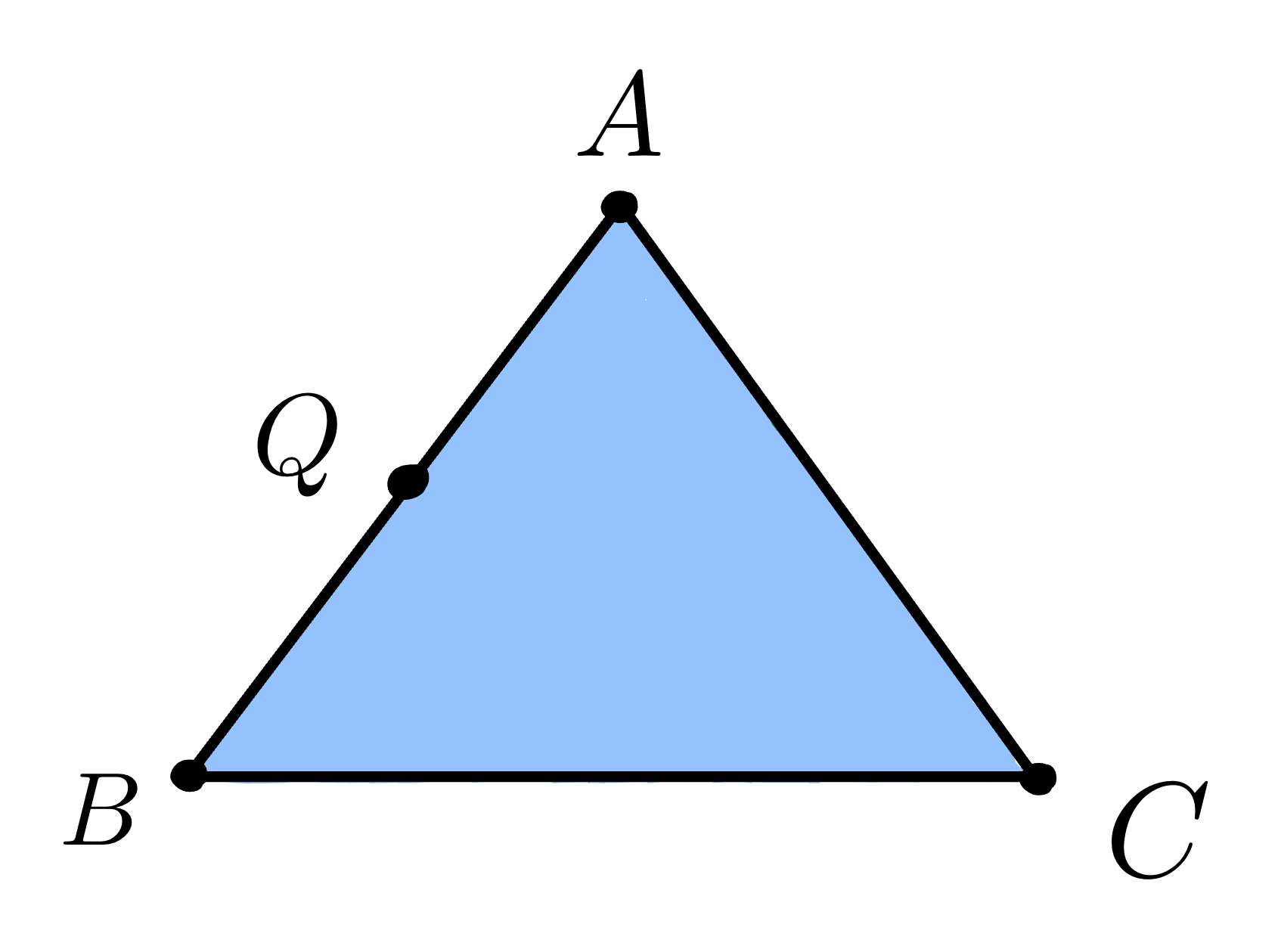

A point \(Q\) that lies on the edge \(AB\) has the form

\[Q = (1-t)A + tB\]where \(0 \leq t \leq 1\).

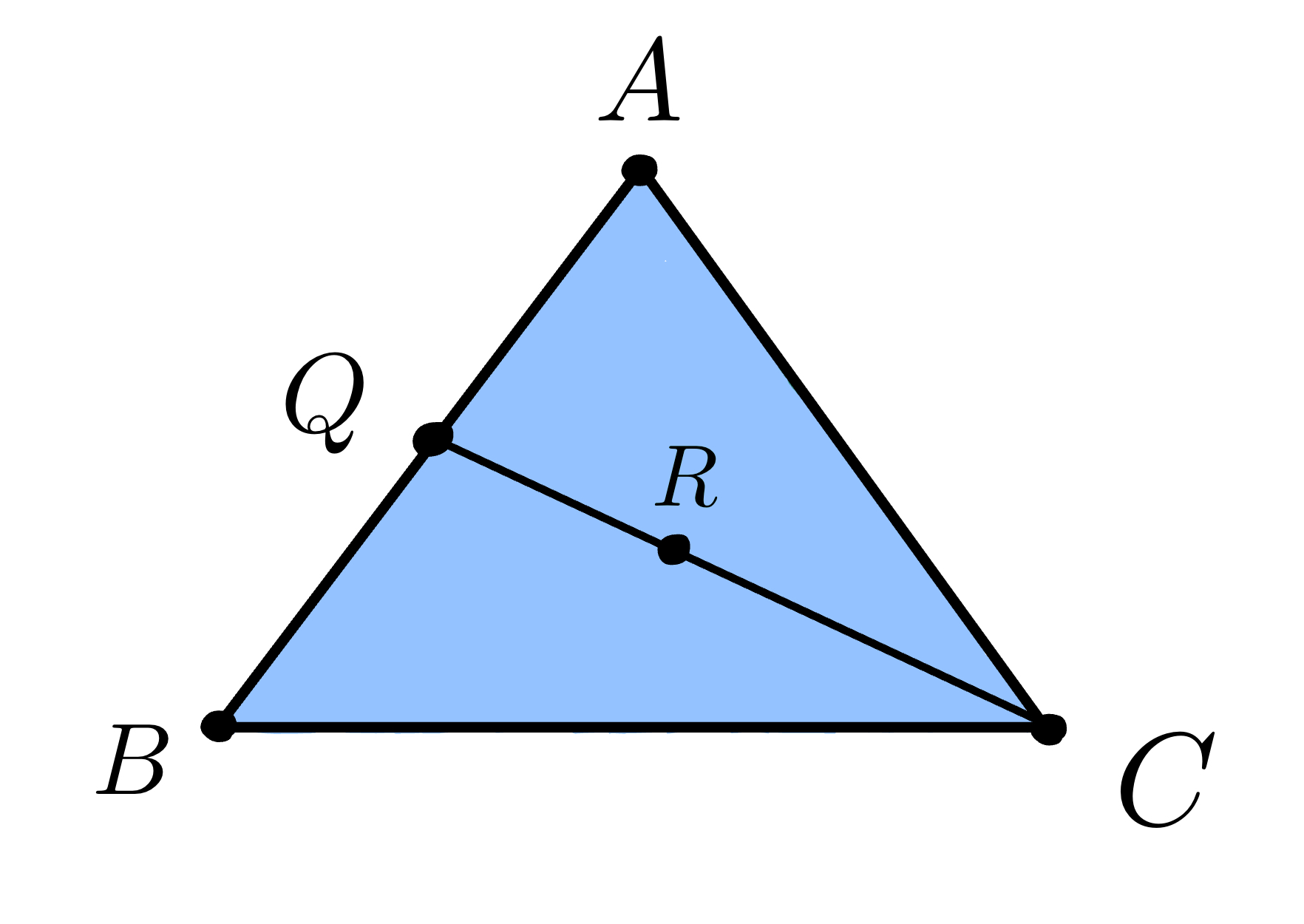

Similarly, a point \(R\) that lies on the edge \(QC\) has the form

\[R = (1-s)Q + sC\]where \(0 \leq s \leq 1\).

We can rewrite \(R\) by substituting the equation for \(Q\). This results in the following equation

\[R = (1-s)((1-t)A + tB) + sC\] \[R = (1-s)(1-t)A + (1-s)tB + sC\]Now, if we sum the coefficients of equation of \(R\), we get

\[(1-s)(1-t) + (1-s)t + s = (1 - t - s + st) + (t - st) + s = 1\]Since \(R\) is an arbitrary point inside the triangle \(ABC\), we can generalize the equation to any point \(P\).

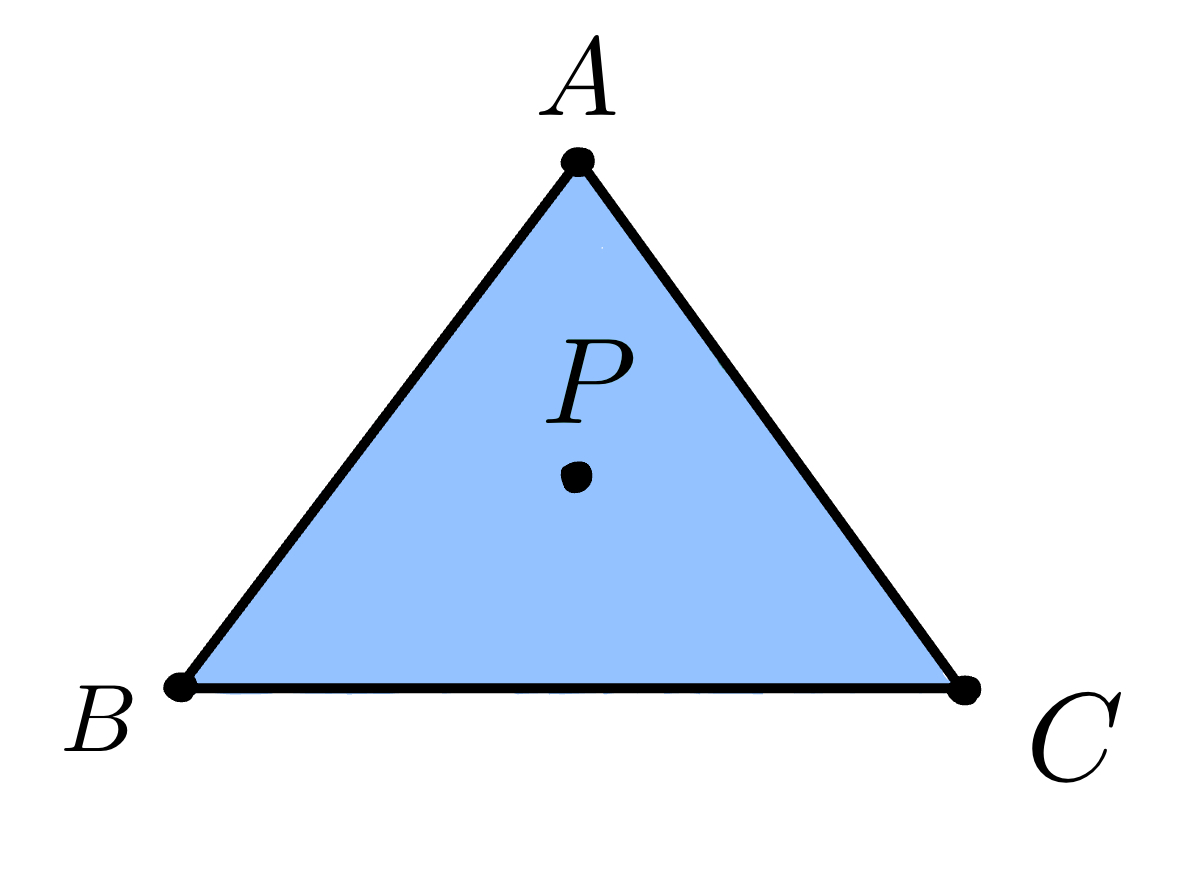

That is, any point \(P\) inside the triangle \(ABC\) has the form

\[P = αA + βB + γC\]where \(α + β + γ = 1\) and \(α, β, γ \geq 0\).

These coefficients \(α\), \(β\) and \(γ\) are called the barycentric coordinates of \(P\) with respect to the triangle \(ABC\), such that

- If \(α = 0\), then \(P\) lies on the edge \(BC\)

- If \(β = 0\), then \(P\) lies on the edge \(AC\)

- If \(γ = 0\), then \(P\) lies on the edge \(AB\).

Calculating Barycentric Coordinates

The equations for calculating the barycentric coordinates are

\[α = \frac{Area(▲PBC)}{Area(▲ABC)}\] \[β = \frac{Area(▲PAC)}{Area(▲ABC)}\] \[γ = \frac{Area(▲PAB)}{Area(▲ABC)}\]The proof for these equations will be explained later in this blog post.

Calculating Area of the Triangle

There are 2 ways to calculate the area of the triangle:

Approach 1

The area of the triangle is

\[Area = \frac{1}{2} \times Base \times Height\]where \(Height\) is the perpendicular shortest distance from the the base edge to the opposite vertex.

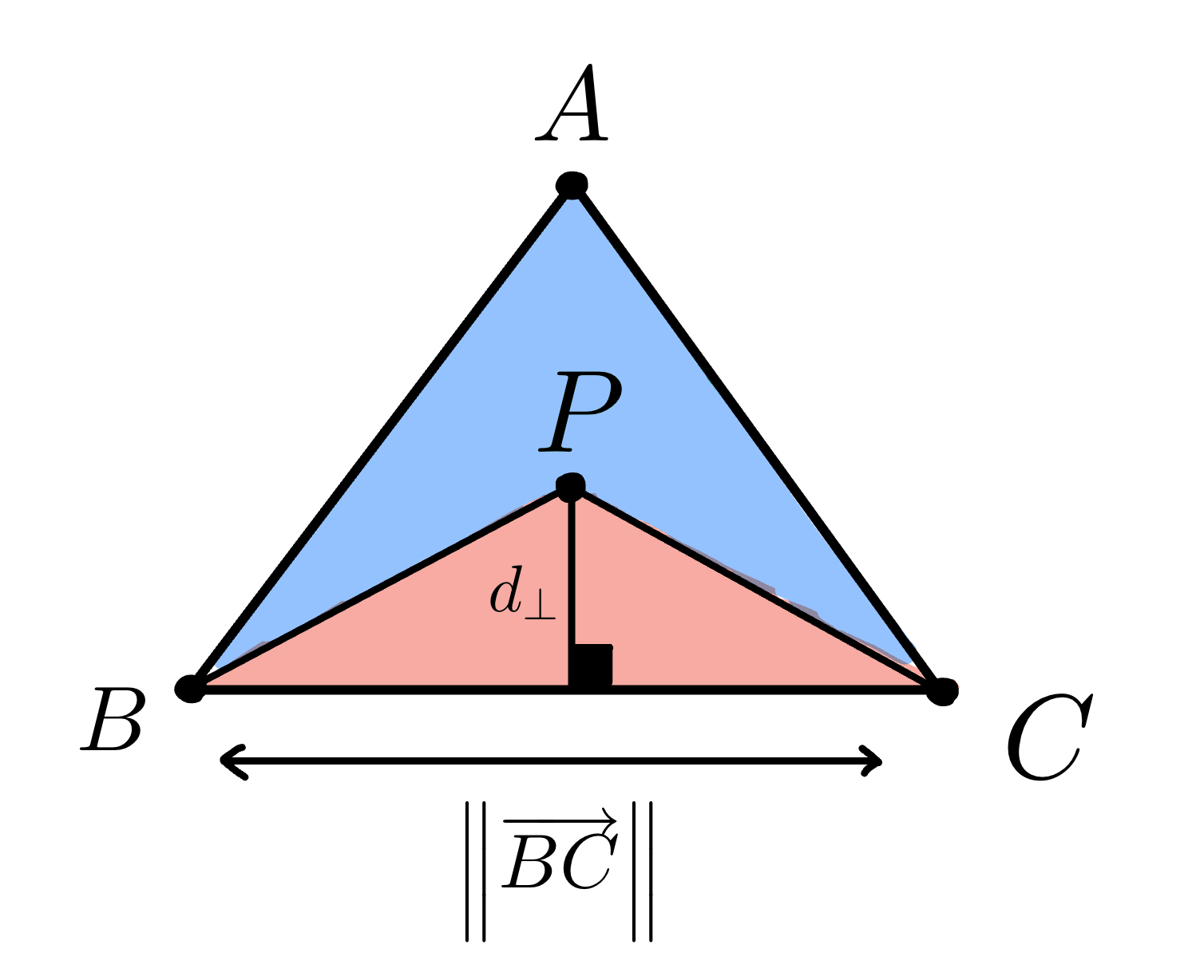

For example, the area of triangle \(PBC\) is

\[Area(▲PBC) = \frac{1}{2} \times ||\vec{BC}|| \times d_{⊥} (P,BC)\]

Approach 2

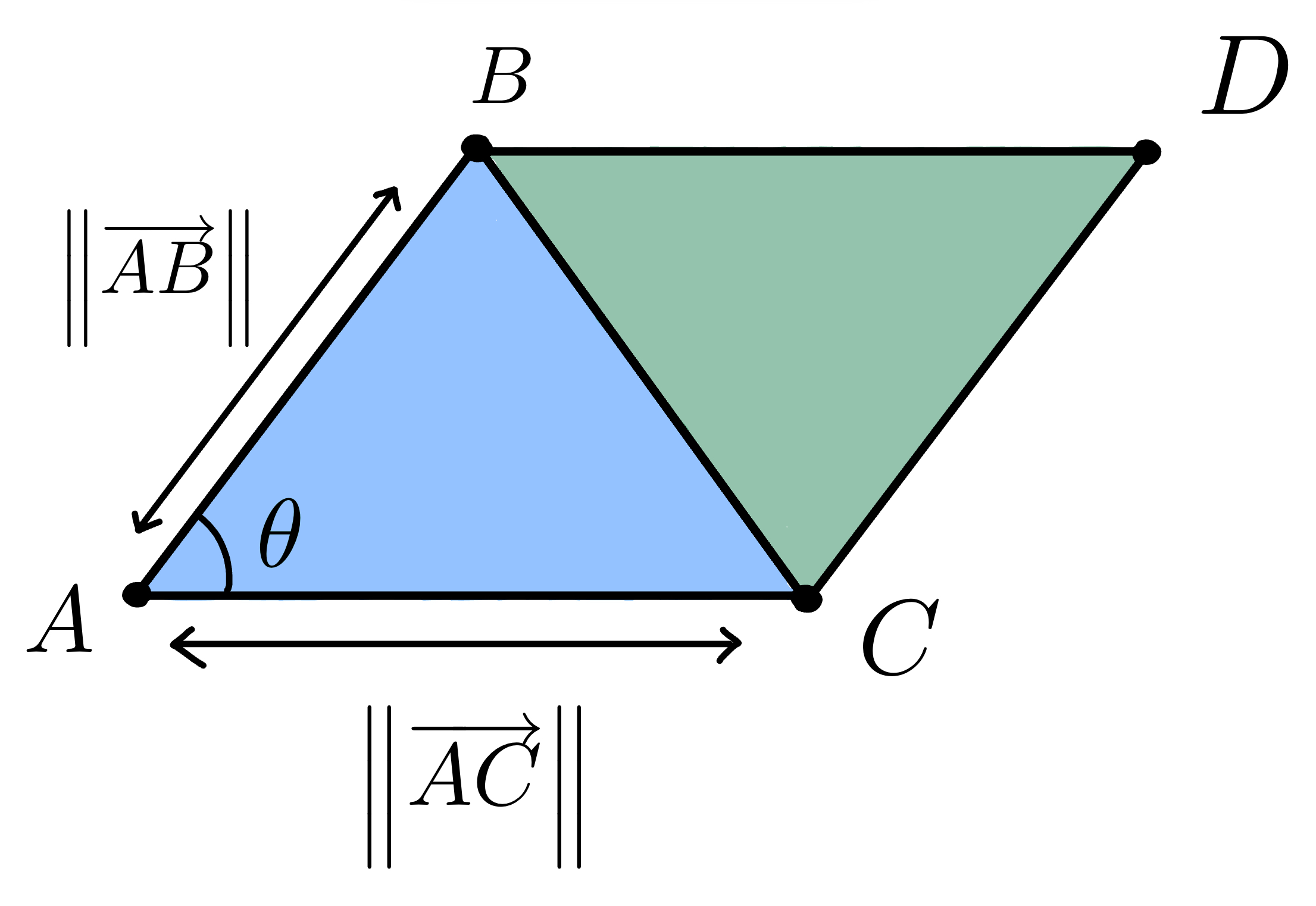

Another easier way to calculate the area of the triangle, is to use the area of the parallelogram.

Consider the parallelogram \(ABCD\). The area of the parallelogram \(ABCD\) is

\[Area(▰ABCD) = ||\vec{AB}|| \times ||\vec{AC}|| \times sin(\theta)\]We can also express the area of the parallelogram \(ABCD\) as the magnitude of the cross product of two vectors that lie on the parallelogram. That is,

\[Area(▰ABCD) = ||\vec{AB} \times \vec{AC}||\]The area of the triangle is equal to half the area of the parallelogram. Hence, the area of the triangle \(ABC\) can be expressed as

\[Area(▲ABC) = \frac{||\vec{AB}|| \times ||\vec{AC}|| \times sin(\theta)}{2} = \frac{||\vec{AB} \times \vec{AC}|| }{2}\]

Proof

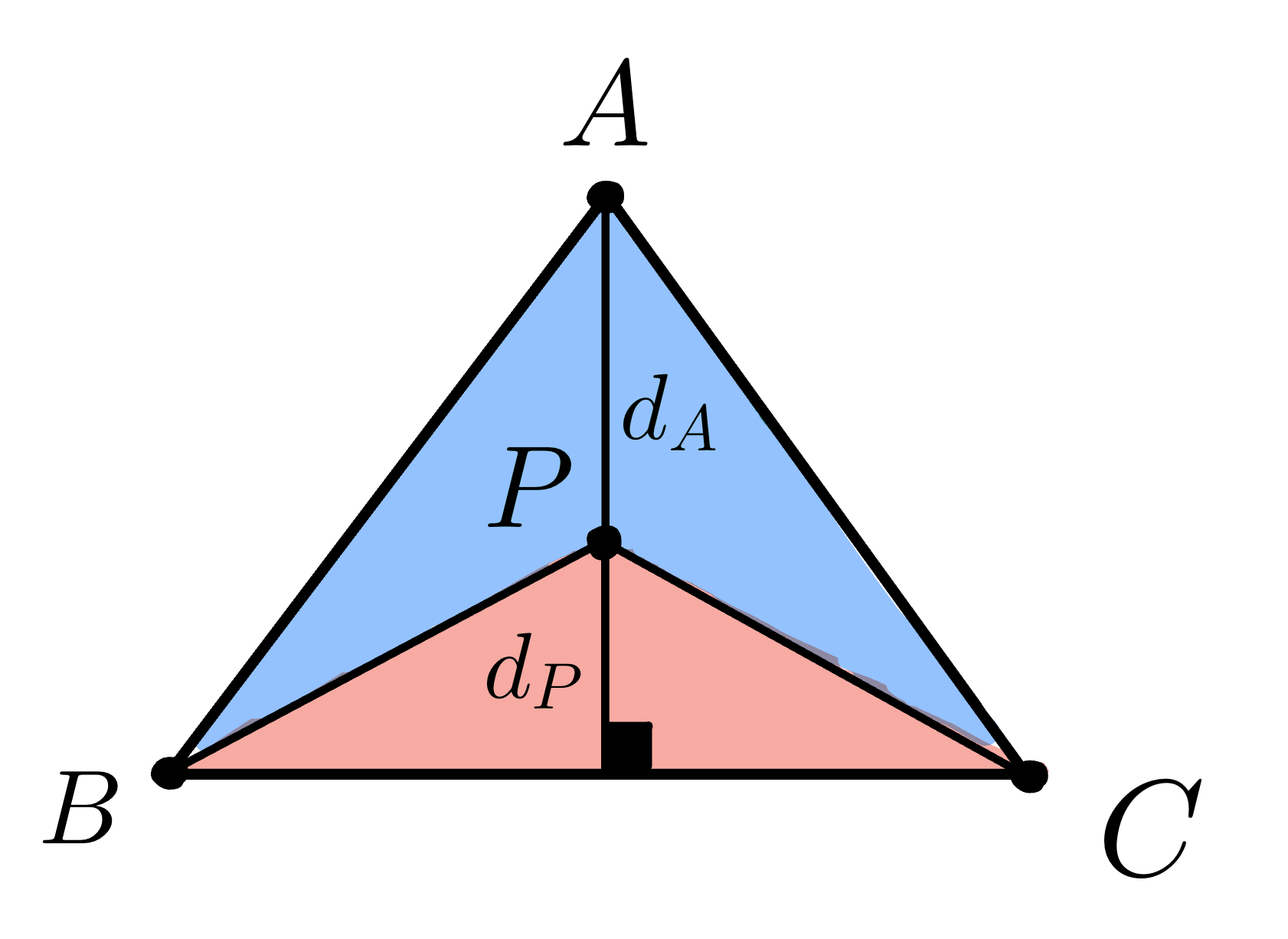

Consider the triangle \(ABC\). Let \(P\) be a point inside the triangle. We know that

\[P = αA + βB + γC\]where \(α + β + γ = 1\) and \(α, β, γ \geq 0\).

We want to prove that

\[α = \frac{Area(▲PBC)}{Area(▲ABC)}\] \[β = \frac{Area(▲PAC)}{Area(▲ABC)}\] \[γ = \frac{Area(▲PAB)}{Area(▲ABC)}\]Without loss of generality, consider the barycentric coordinate \(α\).

Let \(d_P\) be the perpendicular distance from \(P\) to \(BC\) and \(d_A\) be the perpendicular distance from \(A\) to \(BC\).

We know that the area of triangle \(PBC\) is

\[Area(▲PBC) = \frac{1}{2} \times ||\vec{BC}|| \times d_P\]and the area of triangle \(ABC\) is

\[Area(▲ABC) = \frac{1}{2} \times ||\vec{BC}|| \times d_A\]From these equations, we can see that

- \(Area(▲PBC)\) is linearly proportional to the perpendicular distance from \(P\) to \(BC\) ; \(d_P\)

- \(Area(▲ABC)\) is linearly proportional to the perpendicular distance from \(A\) to \(BC\) ; \(d_A\).

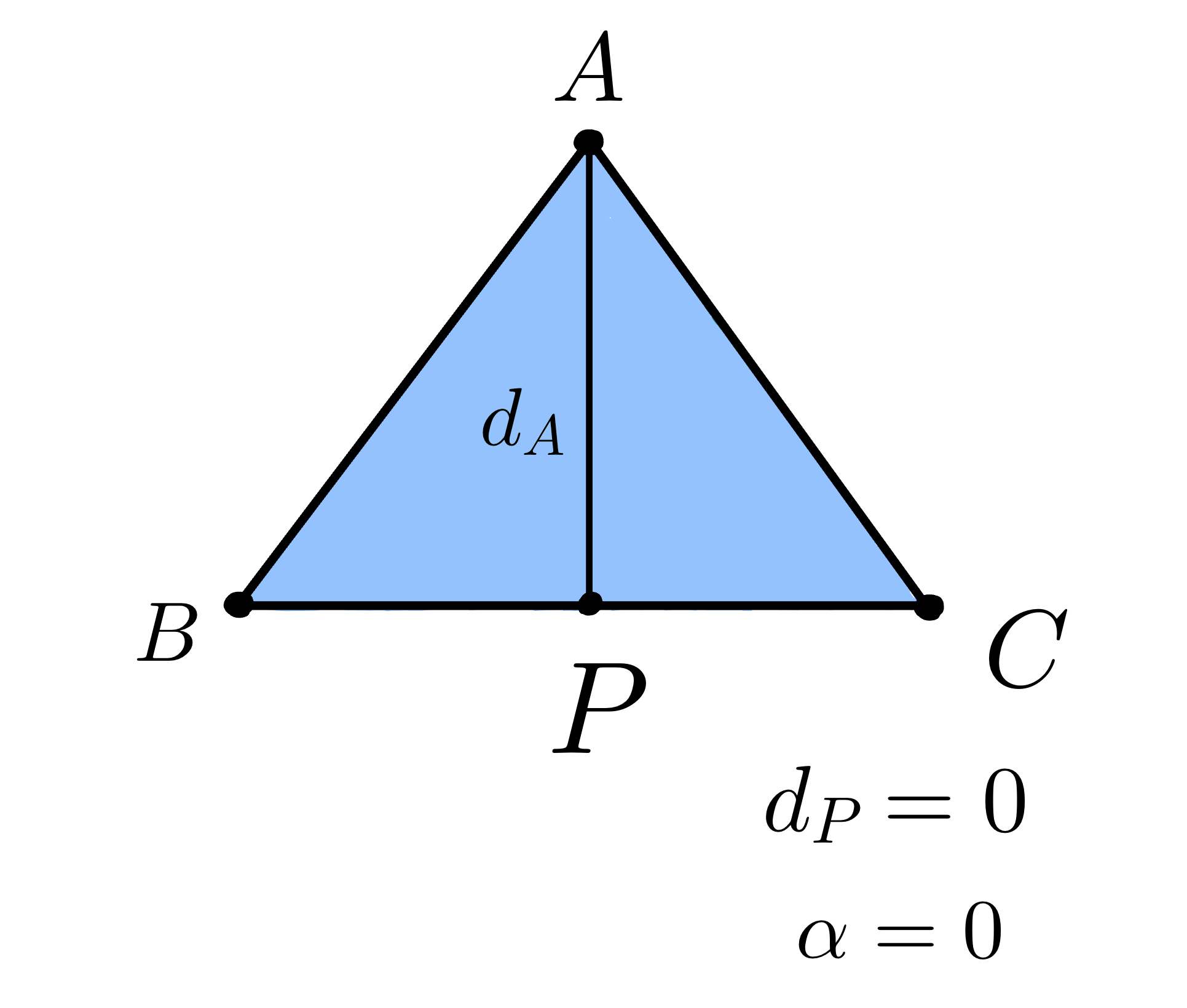

As \(d_P\) decreases, the point \(P\) becomes closer to the edge \(BC\), causing the value of \(α\) to also decrease. When \(d_P=0\), the point \(P\) lies on the edge \(BC\) and \(α=0\).

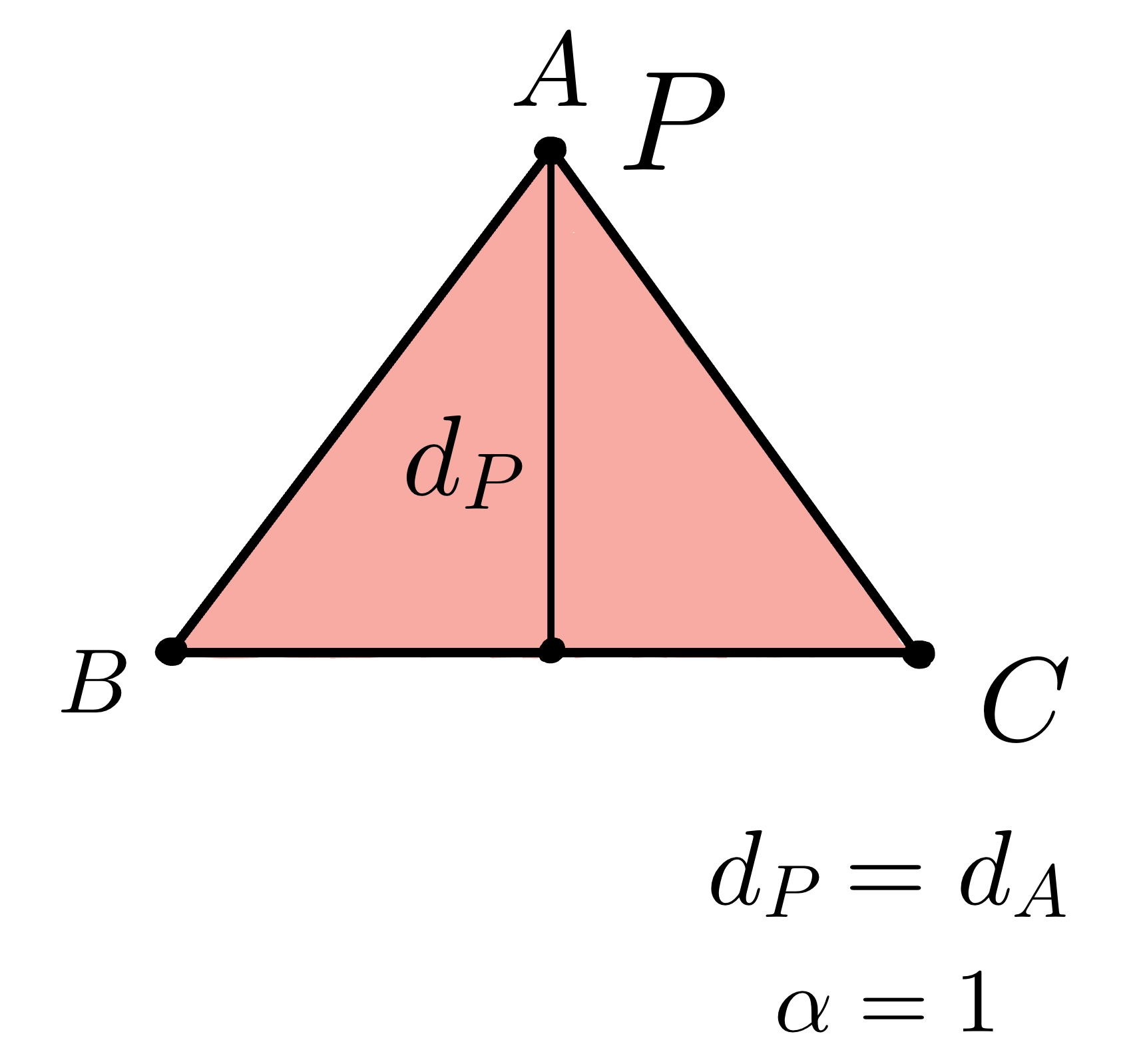

As \(d_P\) increases, the point \(P\) becomes closer to the point \(A\), causing the value of \(α\) to increase. When \(d_P=d_A\), the point \(P\) coincides the point \(A\) and \(α=1\).

This implies that \(α\) is proportional to \(d_P\)

\[α ∝ d_P\]where the proportionality constant is \(d_A\).

That is,

\[α = \frac{d_P}{d_A}\]Since \(d_P\) is linearly proportional to \(Area(PBC)\) and \(d_A\) is linearly proportional to \(Area(ABC)\), then we can rewrite \(α\) as

\[α = \frac{Area(▲PBC)}{Area(▲ABC)}\]By applying the same reasoning to the other two coordinates, we obtain that

\[β = \frac{Area(▲PAC)}{Area(▲ABC)}\] \[γ = \frac{Area(▲PAB)}{Area(▲ABC)}\]Thus, proof is complete.

Applications of Barycentric Coordinates

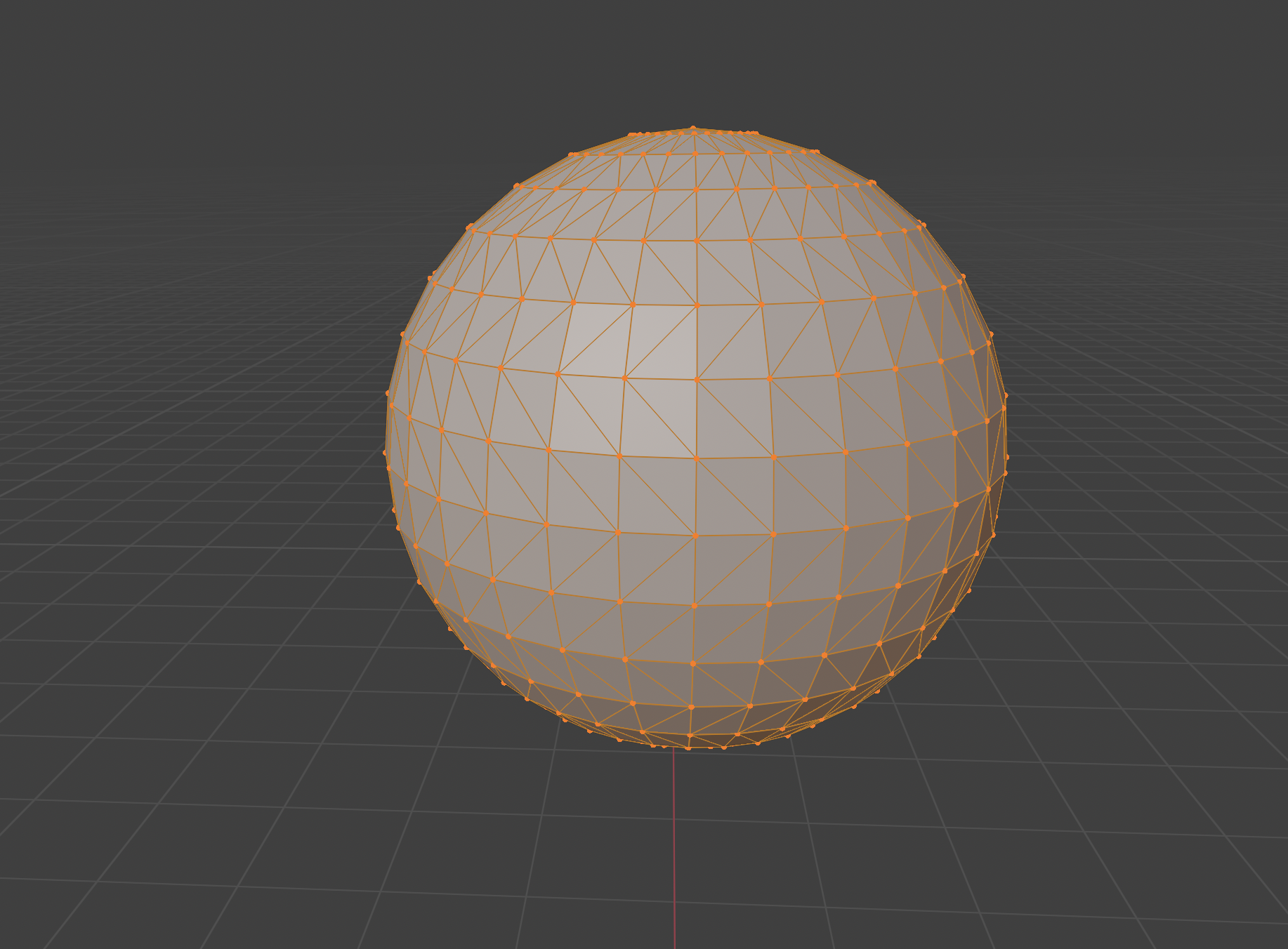

In modern computer graphics, triangles are the fundamental building block for rendering.

All complex geometric meshes are processed in the GPU (Graphics Processing Unit) in terms of triangles.

Regardless of how complex a 3D model is (e.g., spheres, characters, buildings, etc..), it is ultimately broken down into a mesh of triangles that the GPU processes.

Why triangles? Because today’s GPUs (Graphics Processing Units) are highly optimized to handle triangle-based operations very efficiently.

Because triangles are such a widely used geometric primitive, there are many applications for barycentric coordinates.

One of the key steps in the graphics pipeline is rasterization.

During rasterization, the GPU needs to determine whether a pixel is inside the triangle or outside the triangle.

If the pixel is inside the triangle, it will be shaded. If the pixel is outside the triangle, it will not be shaded.

The GPU uses barycentric coordinates \(α\), \(β\), and \(γ\), given the pixel coordinates and the coordinates of each vertex of the triangle, to determine if the pixel is inside the triangle or outside the triangle.

If \(α + β + γ = 1\) and \(α, β, γ \geq 0\), then the pixel is inside the triangle and it will be shaded.

Otherwise, the pixel is outside the triangle and it will not be shaded.

References

- Chapter 7.9.1 - Computer Graphics: Principles and Practice by John F. Hughes

I offer graphics programming services for both students and professionals - including private tutoring and project development for custom games, engines, and real-time applications.

Learn more → Tutoring

Learn more → Project Development